Margaret McNee, McMillan LLP

Margaret McNee, McMillan LLP

On July 1, 2014, Canada’s Anti-Spam Legislation (“CASL”) came into force. CASL applies to all electronic communications sent with a commercial purpose from Canada. Specifically, CASL prohibits organizations from sending commercial electronic messages (CEMs) to an electronic address unless the recipient has consented to receive the message and the sender has provided identification information and an unsubscribe mechanism.

Failure to comply with CASL can result in penalties of up to $1 million for individuals and $10 million for businesses. Directors and officers can also be found personally liable for CASL violations.

In addition, CASL contains a controversial enforcement mechanism known as the “private right of action” that will enable lawsuits to be filed against individuals and organizations for alleged violations of the legislation. Under the private right of action, a court can award (in addition to any actual damages suffered by a plaintiff) up to $200 per breach, to a maximum of $1,000,000 per day, and up to $1,000,000 per day for other CASL violations (such as the prohibition against installing computer programs without consent).

While most of CASL came into force on July 1, 2014, implementation of the private right of action was subject to a three-year delay scheduled to end on July 1, 2017. However, on June 2, 2017, the Canadian government announced that it suspended the coming into force of the private right of action.

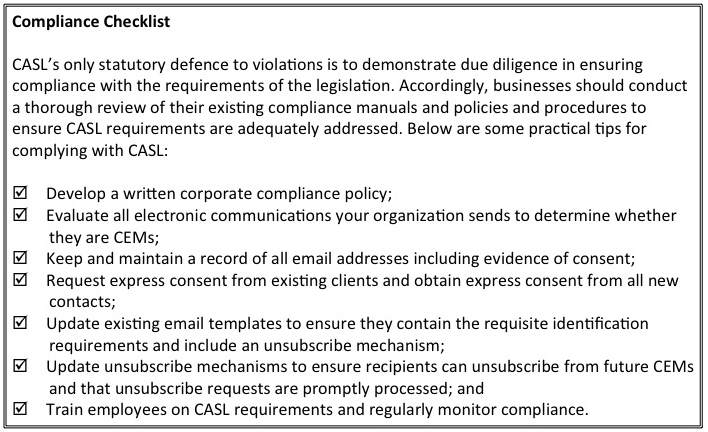

While the postponement provides some breathing room for businesses still working through their CASL compliance strategies, organizations would be well served to use this additional time to review their CASL compliance policies and procedures to ensure that they are comfortably onside with the legislation.

In addition, the transitional provisions, which deemed implied consent for a period of 36 months for organizations sending CEMs based on an existing business relationship, expired on July 1, 2017. Accordingly, the grace period cannot be relied upon for any CEMs sent after July 1.

Consent

Under CASL, a sender must ensure that: (i) prior to sending a CEM, the recipient has consented (either expressly or impliedly) to its receipt; (ii) the sender’s identification and contact information has been clearly provided in the CEM; and (iii) the CEM contains a functioning, easy-to-use unsubscribe mechanism.

Express consent means that a person has clearly agreed (orally or in writing) to receive a commercial electronic message. Express consent requires a recipient to take a positive action to “opt in” to a stated purpose (e.g. clicking “I agree”).

Implied consent, on the other hand, exists in particular statutorily defined circumstances, including where there is an existing business or non-business relationship with the person to whom a message is sent.

Generally speaking, there is an existing business relationship where, within the two-year period immediately before the date on which the CEM was sent, there was a previous commercial transaction with the recipient (e.g. the recipient purchased a product or service from the sender or entered into a written contract with the sender), or within the six-month period immediately before the CEM was sent, the recipient made an inquiry about a product or service to the sender. An existing non-business relationship will be found where the recipient is a member of the sender’s club, association or voluntary organization or has provided volunteer work, a donation or a gift to the sender within the two-year period immediately before the day on which the CEM was sent.

Consent may be implied if:

- the recipient and the sender have an existing business relationship or an existing non-business relationship;

- the recipient has conspicuously published his or her contact information (e.g. on a website) and the publication is not accompanied by a statement that the recipient does not wish to receive unsolicited CEMs and the CEM is relevant to the person's business; or

- the recipient has disclosed his or her email address (e.g. via a business card) to the sender without indicating that the recipient does not wish to receive unsolicited CEMs and the CEM is relevant to the person's business.

One gray area in the legislation is how CASL applies to certain shareholder communications, such as electronic messages containing news releases or company information. National Instrument 54-101 Communication with Beneficial Owners of Securities of a Reporting Issuer permits issuers to use a NOBO list to send securityholder materials in connection with any matter relating to the affairs of the issuer. “Securityholder materials” is broadly defined as any materials that are sent to registered holders or beneficial owners of securities of the reporting issuer. Thus, while the sending of securityholder materials mandated by securities law (such as financial statements, MD&A and proxy-related materials) is acceptable, companies should still obtain prior consent before sending other materials (such as press releases and newsletters), perhaps by having people sign up on the issuer’s website.

Application of CASL

Since its inception, there have been a number of enforcement actions under CASL. For example, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) recently issued a Compliance and Enforcement Decision in which it imposed a $15,000 administrative monetary penalty (AMP) on an individual, William Rapanos, for sending various CEMs without the recipients’ prior consent, the proper identification information or a functioning unsubscribe mechanism. The decision is noteworthy for the CRTC’s consideration of the factors relevant to the determination of AMP amounts, such as an individual’s failure to cooperate during an investigation or to take steps to self-correct.

On a larger scale, however, the decision demonstrates the CRTC’s willingness to issue AMPs even for relatively small-scale violations. And while a $15,000 penalty may seem comparatively nominal, the CRTC has shown that it will not shy away from levying harsher penalties. High-profile fines set by the CRTC include:

- $1.1 million against Compu-Finder for sending CEMs without recipients’ consent or an appropriate unsubscribe mechanism;

- $200,000 against Rogers Media Inc. for sending CEMs without an appropriate unsubscribe mechanism;

- $150,000 against Porter Airlines Inc. for sending CEMs without an appropriate unsubscribe mechanism, proof of recipients’ consent or contact information;

- $60,000 against Kellogg Canada Inc. for sending CEMs without recipients’ consent;

- $50,000 against Blackstone Learning Corp. for sending CEMs without recipients’ consent; and

- $48,000 against Plentyoffish Media Inc. for sending CEMs without an appropriate unsubscribe mechanism.

In addition, in June 2017, the CRTC issued a $10,000 fine against Ghassan Halazon, in his personal capacity as former chief executive officer of Couch Commerce, Inc. and its subsidiaries, for sending CEMs without an appropriate unsubscribe mechanism. This decision is an important reminder that directors and officers cannot escape personal liability under CASL.

Taken together, the above cases demonstrate that both individuals and organizations of all sizes remain susceptible to fines or penalties, and that complying with the fundamental requirements of CASL – consent, identification, and unsubscribe mechanisms – is paramount.

Margaret McNee is a Senior Partner at McMillan LLP. This article was written with the help of Christie Bates, articling student at McMillan LLP in Toronto.