Mark Fattedad, Jarislowsky, Fraser

Mark Fattedad, Jarislowsky, Fraser

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are an ambitious set of 17 goals to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity. With the SDG financing gap estimated to be an incremental US$2-$3 trillion per year,[1] achieving these goals will require a redirection of private capital, in addition to government funding. Sustainable Finance (SF) Bonds are an important innovation and mechanism to connect investor capital with companies and projects that will help close this financing gap. Benefits to investors include a similar risk and return profile as conventional bonds, but with the added bonus of transparency and impact. Benefits to issuers include enhanced reputation, broader investor base, strengthened stakeholder relationships and future proofing the business.

The most common form of SF bonds is ‘green bonds’, where the proceeds are earmarked for climate or environmental projects. For example, proceeds are often used to fund renewable energy projects, public transit development, or energy efficiency initiatives. ‘Social bonds’ are bonds issued to raise capital for projects that reach underserved segments of the population. Examples include Women in Leadership Bonds, and of particular importance right now, pandemic or COVID-19 bonds. These aim to directly fund solutions related to the COVID-19 pandemic such as healthcare equipment or projects aimed at curbing pandemic-related unemployment. ‘Sustainability bonds’ are bonds whose proceeds are used for both environmental and social projects. For example, the World Bank Sustainable Development Bonds finance projects in developing countries aimed at achieving SDGs that span environmental and social issues, such as water treatment projects directed at Goal 14, Life Below Water, and Goal 6, Access to Clean Water & Sanitation. Taken together, green, social and sustainability bonds will play an important role in channeling private capital to finance the transition to a sustainable global economy.

The Canadian Sustainable Finance Bond Market

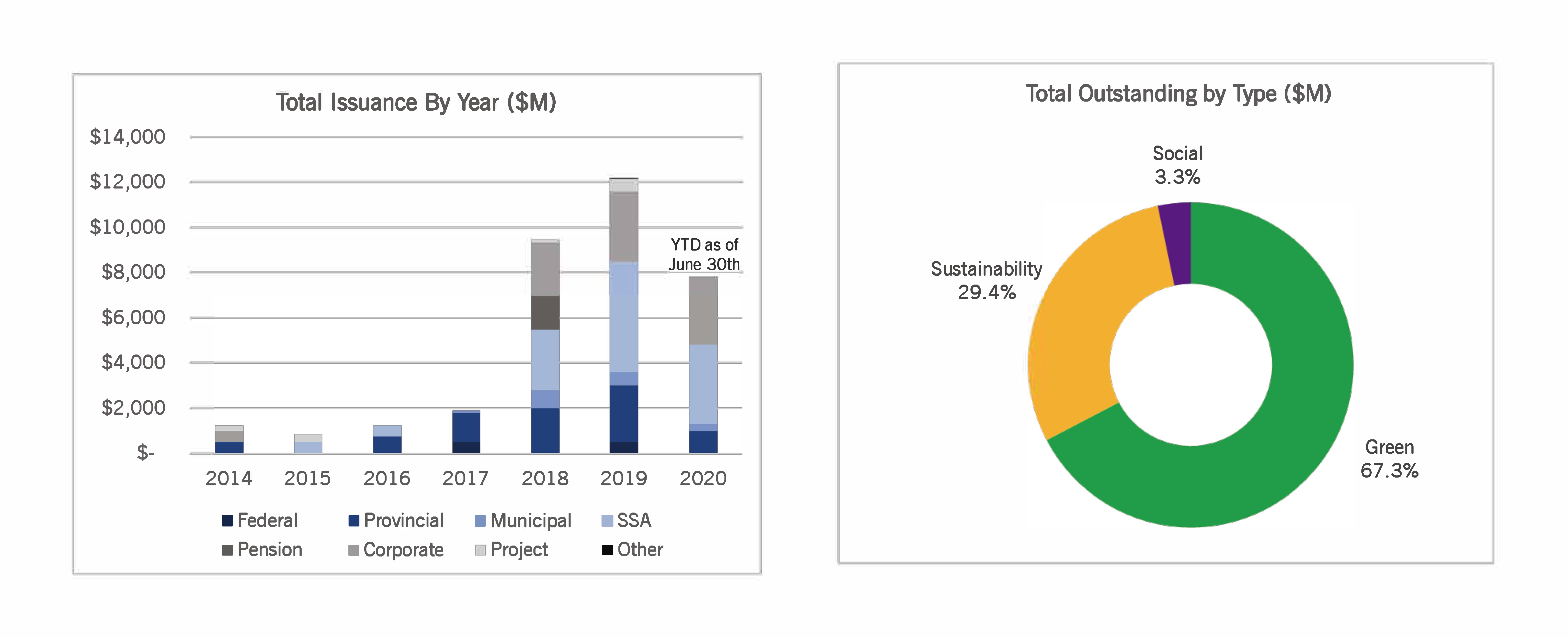

The market for SF bonds has developed rapidly in Canada, with annual issuance growing from $1.2 billion in 2014 to $12.2 billion in 2019. As of June 30, 2020, year-to-date issuance for 2020 was $7.9 billion, putting us on pace to possibly exceed 2019 numbers. In 2019, we again saw sub-sovereign, supranational and agency (SSA) bonds lead the way, with 40% of issuance. The largest issuer was the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (World Bank), which issued over $3.5 billion worth of Sustainability Bonds. The three largest SF Bond issuers in the Canadian market are the World Bank, the Province of Ontario and the Province of Quebec. While this article focuses on public market SF bonds, there is also a thriving ecosystem of smaller private SF bonds, including community bonds and project-specific green bonds.

By type, issuance has been dominated by green bonds at 67%, with sustainability bonds a distant second at 29%. There have been two C$ social bonds issued to date including a $1 billion Women in Leadership Bond issued by CIBC, and more recently, a $100 million issue from The City of Toronto, with proceeds funding affordable housing and shelter development.

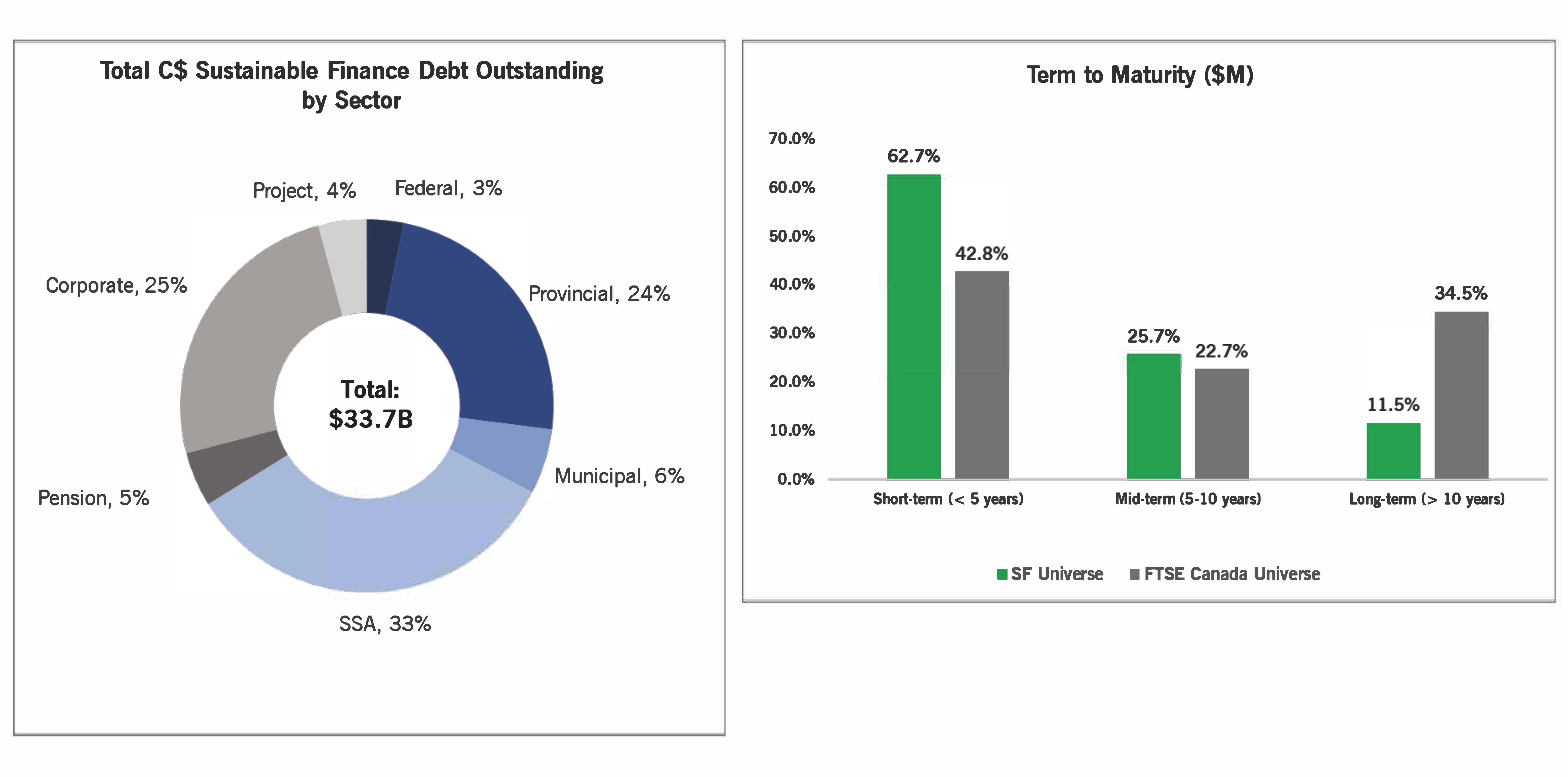

The total C$ sustainable finance bond market is now $33.7 billion, which is impressive but still tiny compared to the total Canadian bond market value of approximately $1.9 trillion. In fact, only 1.6% of the FTSE Canada Universe Bond Index was comprised of SF bonds as of the end of Q2 2020.

Recently, we have seen a growing number of corporate issuers come to market, offering sustainability-focused investors the ability to begin to diversify their sustainable finance bonds by sector. By term structure, the sustainable finance debt stock is more concentrated in shorter-term maturities versus the overall FTSE Canada Universe Bond Index. The weighted average duration for the SF Universe is 5.3 years, versus an average duration of 8.5 years for the FTSE Canada Universe index. As a result, investors would still need to access conventional bonds to optimize risk/return characteristics in a fixed income portfolio.

What’s in it for the Investor?

SF bonds typically have the same credit exposure[2] as the conventional bonds of the same issuer. As a result, green bonds offer investors similar credit risk characteristics, but with the added benefit of transparency and impact. It is this ability to invest in positive change and sustainable development that is the primary driver for investors’ interest in SF bonds. Indeed, the innovation of green, sustainability and social bond labels make the fixed income component of a portfolio a natural starting point for impact-oriented investors, or even mainstream investors wanting to align their portfolios with the SDGs and transition to a low-carbon economy.

Anecdotally, there is some evidence of a small price premium for green over conventional bonds in the emerging Canadian and longer-standing global green bond markets. However, empirical conclusions about the existence of the so-called ‘greenium’ are somewhat mixed, based on the broader global evidence that tries to account for differences in key characteristics such as liquidity, term, optionality, benchmark inclusion and other bond features[3]. Importantly, it does not appear that, on average, there is a material yield discount for green bonds compared to their non-green counterparts. At worst, it appears that green bonds provide a similar risk and return profile for investors, while also increasing the overall resilience of the issuing company and the overall economy through a targeted investment in climate change adaption and mitigation. It seems reasonable to expect a similar trend for bonds with other sustainability themes. In addition, we observed that green bonds provided pockets of outperformance during the pandemic-driven selloff in the first quarter of 2020. This reduced volatility may be because investors were less willing to sell their green bonds. It may also be because dealers were more willing to carry inventory of green bonds for strategic reasons.

Given these benefits, it is no surprise that there is heightened demand for SF bonds in Canada, with oversubscription leaving many interested investors empty-handed. To deal with this oversubscription, many green bond issuers have established rating systems for investment managers and asset owners, evaluating them based on their own sustainable investment policies and track record as green bond market participants. They may then choose to allocate their bonds favourably to ‘dark green’ investors. In fact, when the Province of Quebec issued a green bond in February 2020, it was oversubscribed at a rate of nearly six times, and it chose to allocate 85% of its issuance to investors with green mandates or that were signatories of the Principles for Responsible Investment[4].

What’s in it for the Issuer?

There are additional costs associated with green bond issuance including creating an impact framework, obtaining a second party opinion and the time and effort required to provide post issuance reporting. However, according to the 2020 Green Bond Treasurer Survey[5], issuers broadly perceived these costs to be valid given the benefits noted below. While there is more evidence available on green bonds at this time, we expect many of these points to apply more broadly to SF bonds as well.

1. Enhanced reputation and visibility: Green bonds can form an important piece of a company’s sustainability journey. Put simply, once an organization has developed its sustainability strategy, the issuance of a green bond can provide an important signal to the market, and clearly articulate and highlight tangible elements of a company’s approach to decreasing emissions and increasing resilience to climate change.

2. A broader investor base: 98% of respondents said that their green bond attracted new investors, and “this was particularly true for issuers of bonds normally sold to a predominantly domestic investor base”[6]. This additional depth and breadth can help reinforce and strengthen an issuer’s pool of capital.

3. Strengthening stakeholder relationships: Green bonds facilitate more engagement with investors in conversations regarding the sustainability risks, opportunities and strategy of the business. In addition, green issuance has been found to strengthen internal integration, as the preparation of frameworks and reporting necessarily requires close collaboration among various departments, including Treasury. Most respondents confirmed that issuing a green bond positively impacted their internal commitment to sustainability.

4. Future proofing the business: For example, the process of issuing a green bond includes an internal audit of climate risk exposure within a business, as well as establishing processes for monitoring and accountability for reporting. This can result in a better understanding of both asset and operational climate risk exposure, as well as the identification of new investment opportunities.

Finally, green bond pricing is a subject of ongoing debate, including whether any material pricing benefits exist for issuers. Interestingly, the 2020 Green Bond Treasury Survey suggests that “pricing is one of the ancillary benefits”, but that the above-noted benefits are of greater value.

Looking Forward

As the SF bond market continues to evolve, it presents an exciting opportunity for investors and issuers to come together to focus capital on developing a more sustainable and inclusive future. As the scope of SF bonds continues to expand, investors are rightly concerned with whether the label is truly reflective of the underlying investments. This is referred to as the ‘green integrity’ of the bond. Principles such as the Green Bond Principles have emerged to protect this integrity, and most issuers choose to obtain a second party opinion indicating that they align with established frameworks. Various jurisdictions are also coming out with new frameworks, including the European Union’s new Sustainable Finance Taxonomy.

There are also innovations happening in the space, including bonds with variable coupons based on the achievement of specified environmental or social targets, such as emission reductions. For Canada, the development of a ‘transition bond’ label is of particular interest. Transition bonds are bonds that help emissions-intensive issuers transition to lower-carbon operations through, for instance, the use of carbon capture and sequestration technology in the oil & gas sector. From a high-level perspective, the urgency to act to prevent global warming and importance of these sectors to the Canadian economy represent compelling reasons to move forward with a transition bond label. From an investor perspective, the transition label would facilitate greater choice along the engage/divest spectrum and may contribute to reducing the risk profile of these issuers to the extent that it facilitates a successful transition.

The federal government appointed an Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance to advise Canada’s public and private sectors on facilitating the growth of sustainable finance to speed the transition to a more resilient economy that meets Canada’s climate goals. The panel’s 2019 report Mobilizing Finance for Sustainable Growth contains 15 recommendations, two of which directly relate to SF bonds. They recommend that Canadians be given the opportunity and incentive to connect their savings to climate objectives, and that Canada expand its green fixed income market and set a global standard for climate transition-oriented financing. Tiff Macklem, one of the four expert panelists on sustainable finance who prepared this report, was appointed the Governor of the Bank of Canada in June 2020. This perhaps marks the moment when sustainable finance truly enters the mainstream in Canada.

[2] This is true of Standard Green Bonds, where recourse is to the issuer. Other forms may include Green Revenue Bonds, Green Project Bonds, and Green Securitized Bonds, where the debt is non-recourse and the credit exposure is pledged to specific cash flows or assets.

[3] Zerbib 2017, Ehlers and Packer 2017, Ostlünd 2015, Petrova 2016

[5] 2020 Green Bond Treasurer Survey, Climate Bonds Initiative with analysis support from Henley Business School.

[6] 86 green bond issuers participated in the 2020 Green Bond Treasury Survey between May and November 2019

Mark Fattedad, CFA is Director and Portfolio Manager, Institutional Management, Jarislowsky, Fraser Limited.