Dual class share structures exist when a company issues different types of shares, each class of which typically has different voting and, possibly, dividend rights. Often, these structures are put in place at family-controlled or founder-controlled firms, so the discussion of family firms and dual class shares goes hand in hand: 89% of dual class firms in the Russell 3000 Index have the founding family as owners.

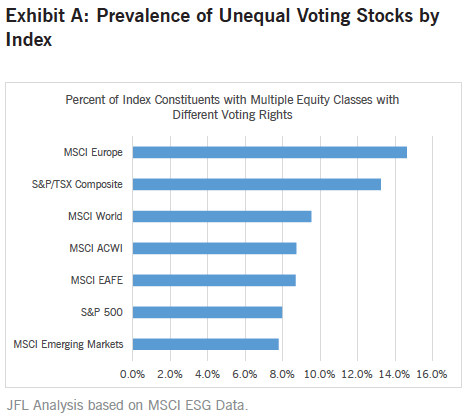

Far from being an anachronism, family-owned businesses and dual class share structures are on the rise globally and remain an important part of global and Canadian markets. As illustrated in Exhibit A, 8.7% of all companies listed on the MSCI All Country World Index have multiple equity classes with unequal voting rights, and the prevalence varies by geography, with it being more common in Europe and Canada. In Canada, family firms and dual class share structures have long been a sizeable component of the economy, with 13.2% of companies listed on the S&P/TSX Composite Index having multiple classes of shares with unequal voting rights and publicly listed family firms accounting for 10 of Canada’s 25 largest employers.

globally and remain an important part of global and Canadian markets. As illustrated in Exhibit A, 8.7% of all companies listed on the MSCI All Country World Index have multiple equity classes with unequal voting rights, and the prevalence varies by geography, with it being more common in Europe and Canada. In Canada, family firms and dual class share structures have long been a sizeable component of the economy, with 13.2% of companies listed on the S&P/TSX Composite Index having multiple classes of shares with unequal voting rights and publicly listed family firms accounting for 10 of Canada’s 25 largest employers.

Globally, the public listing of U.S. technology firms and the growth in emerging market listings are both trends that highlight the importance of multiple share classes. For example, although only 8.0% of S&P 500 constituents have multiple classes with different voting rights, one-fifth of U.S. IPOs in 2017 involved dual class shares.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages of dual class share structures include:

- Access to growth capital for companies without diluting the ability to maintain the long-term vision of the founders/controlling shareholder.

- Allow management to focus on managing the company rather than the short-term interests of some shareholders or hostile takeovers.

- Allow public investors to share in what can be better than average economic value creation from founder-controlled companies that may otherwise remain private.

Disadvantages of dual class share structures include:

- Fewer formal accountability measures aimed at reinforcing alignment with minority shareholders, which can lead to poor outcomes for these shareholders.

- Entrenchment of controlling shareholders that can allow entrepreneurs or families to retain control for longer than beneficial to the company and shareholders.

- Fewer channels of communication between the Board and minority shareholders.

- The lack of shareholder pressure can contribute to a lack of transparency.

Debate: Control versus Democracy

The conventional view, supported by many of the proxy advisory services, is that dual class share structures are contrary to good governance and shareholder democracy. Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis, the two pre-eminent proxy advisory companies, both support the principle of one share, one vote, with Glass Lewis stating that dual class share structures generally reflect negatively on the company’s corporate governance. Both therefore generally recommend that shareholders vote for proposals to eliminate dual class share structures and against proposals to create them, except in the case of strict foreign ownership restrictions that may necessitate them.

Organizations in the United States tend to take a more negative view of dual class share structures than in Canada, with the Council of Institutional Investors submitting letters to the NASDAQ and NYSE asking them to require any newly listed companies with a dual class share structure to impose a mandatory seven-year maximum period before the structure is dissolved (commonly referred to as a time-based ‘sunset clause’).

On the other hand, some argue that a dual class share structure plays an important role in the Canadian context, in that this allows founders to take their companies public without fear that they will be taken over by international companies and turned into ‘branch plants’. Similarly, the idea that a dual class structure allows a company to go public but retain ongoing family control may be appealing in that a family-controlled company may be less susceptible to short-termism and actually be more aligned with shareholder interests. The Institute for Governance of Private and Public Organizations (IGOPP) is a strong advocate of dual class share structures, believing that even time-based sunset clauses would have led many successful Canadian companies to either remain private or to have been taken over by American companies. Without this protection, Canada may miss out on the economic and social value of having family-run companies that remain headquartered domestically. The Canadian Coalition for Good Governance (CCGG) recognizes the argument that mandatory single class shares may prevent Canadian entrepreneurs from taking their companies public, thereby hindering Canadian entrepreneurism, but nonetheless states that utilizing a single class of voting common shares is a best practice.

What does history tell us about the share price performance of dual class share companies?

Overall, the historical evidence suggests that dual class share structures, on average, have outperformed the broader markets for a meaningful period of time. In general, the balance of studies appears to suggest that dual class share structures have at least a non-negative impact on financial performance.

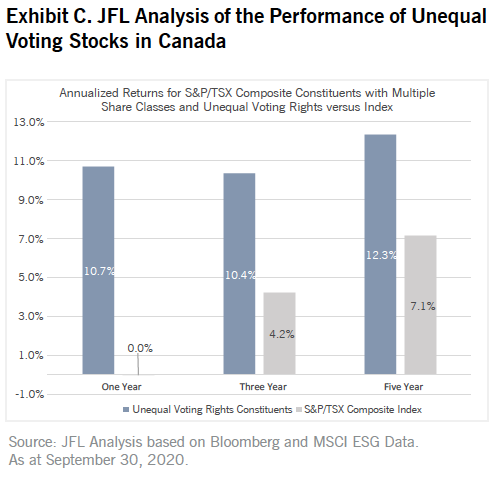

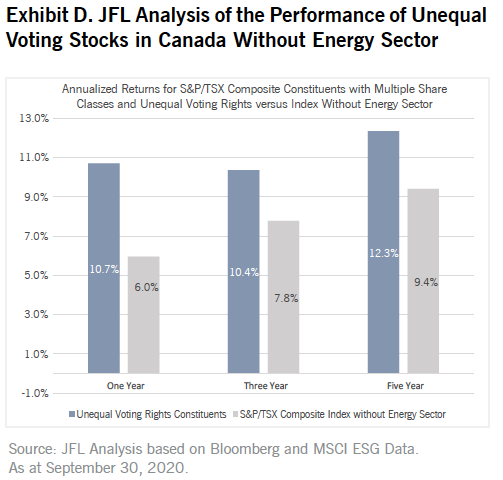

Our own analysis created a market-capitalization-weighted index of S&P/TSX Composite listed companies that have multiple share classes and unequal voting rights. When compared to the S&P/TSX Composite Index as a whole, we found that the companies with unequal voting dual class share structures significantly outperformed the index based on one-year, three-year, and five-year annualized total shareholder return. See Exhibit C. Of course, sector biases play a role: for example, energy and real estate firms are less likely to be family-owned or have dual class share structures, while a growing number of technology and media companies have a dual class share structure. As illustrated in Exhibit D, dual class share companies with unequal voting rights continue to outperform the S&P/TSX Composite Index when the Energy Sector is removed, but the outperformance is less extreme. In the Canadian context, the success of Shopify contributes significantly to the outperformance of dual class share structures, though Shopify may be an example of a company that could have delayed going public if dual class share structures were not an option.

Jarislowsky Fraser’s Stance: Best Practices − Not Dogma

We have seen significant shareholder value created by family-controlled firms with these structures, and, where we find good alignment and practices, we may invest in dual class share companies. Although we generally prefer a one-vote-per-share capital structure, we do not systematically object to a capital structure of subordinate voting shares. Instead, we assess each case individually to evaluate:

- Alignment and behaviour of the controlling party;

- Justification for unequal voting; and

- Mitigants against potential abuse of minority shareholders.

We seek the following best practices:

- We expect ‘skin in the game’, meaning we want management and the controlling shareholder to have significant equity and economic interest, even if it could be asymmetric to their voting power.

- We also seek evidence of aligned compensation that is transparent and focused on long-term performance.

- One element we do believe should be mandatory is coattail provisions, which would ensure equal treatment and tag-along rights for any M&A activities.

- In general, we advocate for some level of formal accountability and communication between the Board and all minority shareholders, such that all common shares have some voting rights (generally supporting a maximum 4:1 voting ratio).

- In terms of Board independence, we seek a strong and suitably empowered Independent Chair or Lead Director, and expect the total number of directors on the Board to be proportional to voting interest up to two-thirds for the controlling shareholder. However, if the controlling shareholder is related to management, we expect the Board to be two-thirds independent.

- We also look for majority independent committees with independent committee chairs, and note that committee independence is particularly important for Audit and Compensation Committees.

- Other than for foreign ownership rules, we believe that dual class shares should represent a transitional phase between private and full public ownership. We see value in entrepreneurs retaining control of their company but generally believe that rationale for the dual class share structure diminishes once the founder is no longer meaningfully involved. For this reason, we believe it important that the dual class structure should not automatically extend beyond the entrepreneur’s tenure, instead requiring periodic subordinate shareholder approval to maintain the structure once ownership and/or involvement declines significantly. We generally believe that these ownership-based sunset clauses will better serve the interests of long-term investors than strict time-based sunset clauses.

- Although not an absolute requirement, we see significant value in a periodic review of the dual class share structure at appropriate points in the life cycle of a company to ensure alignment with future objectives and needs. Overall, we strongly believe that the onus is on management and the Board to regularly justify the structure to shareholders.

Big Tech: Who is in charge of the internet?

The role of dual class share structures in rapidly emerging and potentially disruptive sectors like tech is a growing trend with more than one-third of tech IPOs going public with some kind of dual class share structure. The WeWork failed IPO (contemplated to have the founder with a 20:1 advantage in voting rights) and subsequent restructuring highlighted how less accountable governance and poor alignment of management can drive poor shareholder outcomes.

On the other hand, the recent outperformance of companies like Shopify, Facebook, Google and Zoom, all companies with dual class shares, matched their rapid rise in importance in society during the pandemic. Many suggest that the rapidly evolving nature and volatility of these fast-growing and innovative industries require a firmer, longer-term steward that may be difficult to get with widely distributed and liquid voting rights.

Ultimately, we believe that there are ways for management and the Board of fast-growing, dominant tech companies to expand their capacity and accountability and to balance innovation and long-term vision with agency and scale issues in a timely and orderly fashion through:

- Sunset clauses/dilution triggers: These are provisions that convert all shares to a single class after a specific time period or change in the controlling shareholder holdings or identity. More recently, there have been proposals for a periodic review that allows subordinated shareholders to vote to approve an extension of the dual class share structure beyond a certain date, ownership or involvement threshold.

- Financial alignment with long-term shareholder outcomes: Three important markers of financial alignment include high equity ownership, aligned compensation and percentage of net worth.

- Value of diversity: A culture that values and encourages greater diversity and independence on Boards and the organization as a whole can have better outcomes. An example of this could be Facebook’s recent Board additions of women with diverse life and industry experiences.

- Independent advice and counsel for the Board on key issues: Examples of this are Google’s external advisory Board on Ethical AI use and Facebook’s Safety Advisory Board. These can provide improved representation of stakeholders that support the value of the platforms, broader insights on key issues and a general sounding board for CEOs and Boards that are clearly brilliant but may not have the (lived) experience necessary to recognize or manage complex and rapidly evolving social issues in a timely and appropriate manner.

This article is an excerpt from: The ESG Files: Dual Class or Second Class? Jarislowsky Fraser, January 2021.