In May 2015, when Halifax-based Centennial Group pushed for Board change at Temple Hotels, the predictable proxy contest never materialized. Instead, within just a few weeks’ time, the dissident shareholder and the company negotiated a mutually satisfactory arrangement and rescheduled the annual meeting to accommodate the nominee changes. “The two moved to something quickly that was amicable for both sides,” says Amy Freedman, President at Kingsdale Shareholder Services in Toronto. “You could call this a more ‘constructivist’ approach.”

The Centennial/Temple agreement is emblematic of a new trend in Canadian shareholder activism: a tendency for private conversations to yield results before a messy, public battle ensues.

“2015 was more of a behind-the-scenes activism year in Canada,” says Freedman. “People don’t realize that there’s far more activism than anybody sees, but it’s resolved before a white paper appears or the public even knows.”

Orestes Pasparakis, Partner and Co-Chair of the special situations group at Norton Rose Fulbright in Toronto, describes 2015 as a busy year for activism, and he, too, points to what he terms “quiet activism.” Quiet activism, he says, may result in a company making accommodations to satisfy an activist – or the company might respond so forcefully that the threat evaporates. “Some companies,” he says, “demonstrate that they won’t be an easy target by pushing back in a significant way very quickly. And thus the activist goes away and picks another target.”

Pasparakis believes that Canadian activism has now reached its adolescence. “We see activism occurring a lot, and we see companies worried,” he says. And increasingly, he finds, investor relations professionals are playing pivotal roles in helping companies deal with activist scenarios.

Ankle Biters Versus Serious Activists

Know your shareholder – the first law of investor relations – is a particularly powerful message for IROs confronting an activist situation.

Pasparakis urges IROs to identify disgruntled shareholders early. “As an IRO,” he says, “you want to have the kind of relationship with your shareholders that the minute they hang up the phone with somebody from an activist hedge fund, they pick up the phone and call you and say: ‘I got a very interesting call from so-and-so.’”

What’s more, savvy IROs should distinguish between unhappy investors with an axe to grind and those who pose a serious threat to the future of the company. Pasparakis describes activists in the first camp as “ankle biters,” or people who “are going to cause difficulties with letters to the Board and time with the CFO, but at the end of the day, they don’t have the makeup or the moxie to bring on a fight.” He continues: “You want to make sure that you don’t react in a knee-jerk way to shareholders who seek to shape change through threats when they don’t really have the desire to see those threats through.”

Hooman Tabesh, Executive Vice President and General Counsel at Kingsdale, draws a similar distinction. He notes that “newbie activists trying to make a name for themselves” are often satisfied by placing a single director on a Board, while the Pershing Squares and JANA Partners of the world “won’t go away unless they make substantive changes at companies.”

Although no two activists are the same, it’s extremely unwise to underestimate activists as a whole. “Nowadays, we hear from activists well in advance of their approaching a target to study the vulnerability of that target,” says Tabesh. “Activists in Canada are becoming a lot more sophisticated.”

Board representation is no longer the only strategy Canadian activists are pursuing. Increasingly, activists are using their muscle to oppose M&A transactions. David Salmon, President of Laurel Hill Canada, notes that in 2015, retail-led opposition to an M&A deal between Denison Mines and Fission Uranium resulted in the deal being terminated, while a merger between Batero Gold and CB Gold was opposed by a shareholder and later defeated. Similarly, a transaction between Pacific Rubiales Energy Corp. and Mexican conglomerate Alfa SAB met with shareholder opposition and did not receive the support necessary to succeed.

Of course, shareholder opposition doesn’t always bring a deal to a grinding halt. Last year, says Salmon, Crescent Point Energy’s acquisition of Legacy Oil and Gas was opposed by FrontFour Capital and yet ultimately garnered enough shareholder support to go forward. Whether or not a given deal goes through, the point remains the same: Shareholders at Canadian companies are refusing to rubber-stamp large transactions without careful consideration.

Thinking Like an Activist

Now that Canadian Pacific Railway, TELUS, and Agrium, Inc. have all been targets of high profile shareholder campaigns, Canadian IROs realize that no company is immune to activist attack.

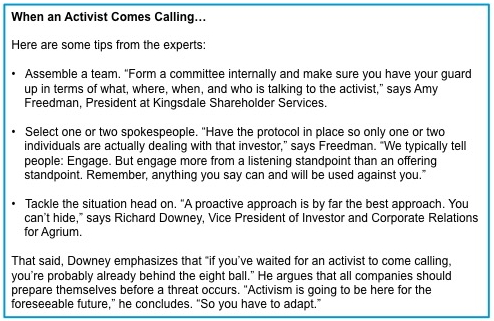

Richard Downey, Vice President of Investor and Corporate Relations for Agrium, puts it this way: “It doesn’t matter whether you’re Apple, Microsoft, or Agrium, there are very few companies that haven’t had an activist in their company looking for something.”

Downey advises companies to evaluate their own potential as an activist target by examining share performance, the business mix, and the reputation of management and the company more broadly. “It’s worthwhile putting on the lenses of an activist and looking at all your materials and actions to evaluate if you’re doing everything you can in case you’re targeted,” he says.

Also, Downey warns IROs to carefully consider the wording of annual reports, proxy statements, and roadshow presentation scripts since “if you go to a proxy contest, everything you’ve ever written will become fodder.”

Laurel Hill’s Salmon urges IROs to speak with their shareholders about hot-button governance issues, such as advance notice policies, shareholder rights plans, enhanced quorum requirements and the bylaws on third-party compensation for directors. “The Board doesn’t always have to comply with what are seen as the best governance practices out there,” he says. “The Board has to do what’s in the best interests of the company – but you certainly want to have a clear and well-thought-out response.”

He continues: “Professional activists are very sophisticated and very skilled. In many cases, they’ve done a review that’s far more in-depth than what your Board knows about your company. Hear some of the key concerns, and make sure you stay ahead of the curve.”

Arguably, preparation is a very effective defense tactic. “Activists are looking for the low-hanging fruit,” says Salmon. “If they know an investor relations officer is talking about trends within the broader industry, the governance industry, and the activism space, they quite possibly may move on to a firm that doesn’t have the same level of dialogue and discussion with key investors.”

The Heightened Role of IR

Pasparakis notes that a skilled IRO can preempt activist campaigns by communicating deeply and intelligently about long-term strategy. “If you’ve communicated the strategy well, and shareholders understand it, when somebody comes along with a new strategy, the IRO can say, ‘Of course we thought of this, and here’s the reason why we’re continuing with the strategy we told you we’re going to pursue.’”

He continues: “If the investor relations person has not articulated a clear strategy and vision to shareholders, then the ideas of an activist may seem to be the only ideas and vision a company has.”

Beyond communications strategy, Freedman emphasizes that an IRO’s longstanding knowledge of shareholders can make an enormous difference. “If you know in your pocket which shareholders you have and which you don’t, you can fight from a position of strength,” she says. “Therefore, elevating the IR role is critical. And as an IR professional, [learning and communicating about activism] is a way to make yourself invaluable to your company.”