It was a notable date: on December 31, 2014, the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) began requiring public companies to disclose the number of women on their Boards, how women are identified and selected for Board seats, and what renewal or term-limit mechanisms are in place.

“[Diversity] is something we’ve had and thought about for a long time, so our diversity policy was really just a formal articulation of practices,” says Rachelle Girard, Director of Investor Relations at Cameco Corp. “We went a little further than what was required because when our Board thinks about diversity, it’s more than just gender.” Cameco's proxy circular now boasts a description of the number of women on the Board, as well as directors’ ethnic diversity, geographic representation, age, skills, and experience.

“It’s our belief that diversity leads to a broader range of questions being asked in meetings, and ultimately in better decision making,” says Girard.

The new CSA requirements, enforced by the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC), came out of a public roundtable and survey of TSX-listed companies. The OSC received responses from 448 companies and 57% had no women directors, while almost 90% did not disclose the proportion of women employees in their organizations.

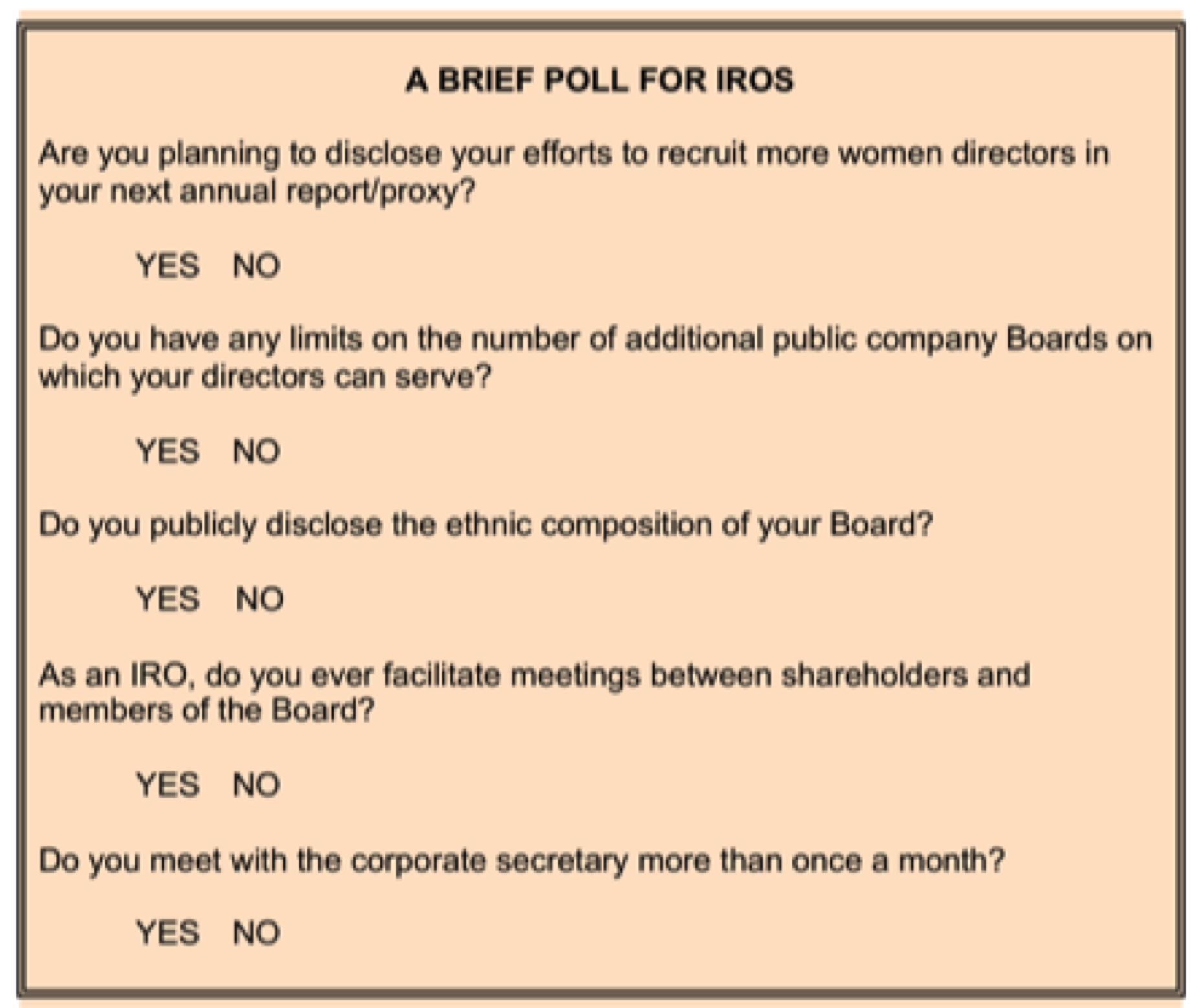

Board composition has not traditionally fallen within the IRO's bailiwick; however, these issues are now so prominent that IROs may be asked questions about the Board at a level of detail never before encountered.

“The concept of diversity, particularly gender diversity, is a question I’d expect would be asked of companies by their shareholders,” says Andrew J. MacDougall, Partner at Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP in Toronto. “It’s something that as a society we all have an interest in, and so I think these questions will come up.”

Diversity Issues

Sylvia Groves, President and Creative Director at Governance Studio in Calgary, points out that the Canadian model of disclosing gender diversity, known as “comply or explain,” does not have “quite as much teeth” as regulations in the U.S. and elsewhere. “The Boards here are not required to do anything. But if they’re not doing anything, they’re required to explain why they’re not doing anything,” she says.

One reason why public companies may not be flocking to add more women to their Boards is that the studies assessing the benefits are often inconclusive.

That said, Groves finds studies compelling that show diverse Boards address CEO underperformance more quickly and effectively. “Given that CEO underperformance is one of the biggest, most difficult things Boards have to deal with,” she says, “I’m amazed that shareholders aren’t pounding down the doors and saying we need diversity. Because if the CEO is going off the rails, a diverse Board is going to do something about it.”

The early effects of the OSC's new disclosure regimen have not been particularly heartening. In September 2015, the CSA released Multilateral Staff Notice 58-307, which looks at the first year of disclosure under the CSA rules. The OSC held a roundtable to review results and found that 65% of the 722 companies reviewed had not adopted a written policy on Board gender diversity.

In an Osler report entitled, Women in Leadership Roles at TSX-Listed Companies: Diversity Disclosure Practices, MacDougall found that the most often expressed reason for not adopting targets for women on the Board is that companies “do not want to compromise the principles of a meritocracy.” And even for those companies that do set targets, the most popular target was just 25% female representation on the Board.

MacDougall believes that the next round of disclosures may be stronger because the banks, which typically have fiscal years ending October 31, will be included in the overall sample. “Banks have been the leaders in this area because it’s been a key issue for financial institutions for a much longer period of time,” he says. In addition, MacDougall emphasizes: “We’re getting some best practice disclosure out there that will hopefully raise the bar for next time.”

“There’s more work to do in doing a better job of disclosure in that area,” agrees Steve Erlichman, Executive Director of the Canadian Coalition for Good Governance (CCGG).

Although some have suggested that the problem is poor disclosure, Erlichman notes that low numbers of women on Boards is “a substantive issue, not just a disclosure issue.” He also says that while gender diversity is important, so are other types of diversity, including diversity of skill sets and geography. In its report Board Gender Diversity, CCGG summarizes research showing that diverse Boards are “more likely to avoid ‘group think’” and lead to more independence and a better ability to oversee and mitigate risk.

Cameco’s Girard, for instance, says that when it came time to highlight gender diversity, her company decided to voluntarily include other types of diversity, including ethnic. “The majority of our production comes out of our facilities in northern Saskatchewan, which is where we draw the majority of our workforce, as well,” she says. “Our Board has long believed we needed a Board member with Aboriginal background to make sure we really understood the culture, the heritage, values, beliefs and rights of these people.” Including an Aboriginal perspective plays an important part in building and maintaining what Girard describes as her company’s “social license to operate.”

Overboarding and Refreshment

Starting February 1, 2017, ISS in Canada will change the definition of an ‘overboarded’ director to one who sits on more than four public company Boards (six is the number of Board seats that ISS now deems too many). ISS will only recommend a vote against a director if he or she is overboarded and attends less than 75% of Board meetings, but cautionary language will be included in ISS reports where directors are overboarded, regardless of attendance.

“This will cause issues for some directors because there are a number of professional directors who sit on numerous Boards,” says Mike Devereux, Partner at Stikeman Elliott LLP in Toronto.

MacDougall points out overboarding is a particularly acute problem because “the demands on the Boards of directors in terms of time and commitment have increased.” He continues: “It’s not realistic that individuals on too many Boards will be able to devote the same time and attention to each of the Boards on which they sit.”

When it comes to overboarding, Groves emphasizes that an IRO should know the backstory. “The reality is that some people are ‘overboarded’ with one Board. It’s too much for them,” she says, noting that other individuals can successfully juggle a much larger workload.

Groves points out that another emerging Board issue is term limits, or whether there should be a specific tenure for directors. She says research has found that once directors have sat on a particular Board for nine or more years, “they’re actually not adding value any more because they’re too close, they’re now captured by management, and they are not as willing as a diverse Board to say, ‘Hey, I think the CEO is going off the rails, let’s talk about this.’”

In addition, Groves points out that achieving diverse Boards is particularly challenging without some type of term limit because new seats so rarely open up.

Whatever an IRO thinks of prevailing wisdom on term limits or diversity, familiarity with the issues is critical.

“An IRO needs to understand the Board composition, and an IRO needs to understand the Board’s skills,” asserts Groves. She notes that a few years ago, Jana Partners sought to take over Agrium Inc. and took aim at the company for a lack of pertinent Board skills. Agrium responded by disclosing a raft of new directors’ skills, and the plan backfired because these skills had not previously been mentioned and therefore looked suspicious. “If an IRO doesn’t know what the Board’s skill set is and why that skill set may have changed from year to year, there’s a chance to get caught flatfooted if there’s an activist involved,” she says.

The IRO’s Role

Jennifer F. Longhurst, Partner at Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg LLP in Toronto, notes that shareholder engagement is increasingly important – and yet there are no one-size-fits all solutions. “Engagement goes beyond the outward communication from the company,” she says. “Institutional shareholders, especially the large ones, are expecting to have avenues, both formal and informal, for conveying their perspectives on different issues.”

The Institute of Corporate Directors (ICD) in Canada published guidance on March 7, 2016 to help public companies develop a shareholder engagement approach to corporate governance. Among the recommendations is “know your most significant investors,” a task with which the IRO is uniquely positioned to assist. The ICD guidance is available here: https://www.icd.ca/Resource-Centre/Policy-on-Director-Issues/Position-Papers/ICD-Guidance-for-Director-Shareholder-Engagement.aspx.

Longhurst cautions that shareholder engagement is a tricky issue because each investor wants his or her own brand of interaction. “There’s a tendency to treat shareholders as a monolithic class, as if everybody wants the same thing,” she says. “But shareholders are showing themselves to be a lot more nuanced and sophisticated.”

Since IROs have developed longstanding relationships with a variety of institutions, they have a major role to play when it comes to explaining Board issues. “The way IROs serve their clients in today’s world has changed significantly,” Longhurst says. “I don’t think the role is only outward looking, but rather the role has evolved into facilitating a two-way dialogue and addressing a whole host of governance issues beyond just typical financial and business matters.”

One of the best ways to stay up-to-date on these issues is to forge a strong relationship with the corporate secretary’s office. In many instances, the corporate secretary is the best and most accessible path to a deep knowledge of directors and their unique backgrounds and skills. In turn, IROs are ideally situated to share their knowledge of institutional investors and what their precise shareholder engagement desires might be.

“I think that investor relations professionals are often underexposed to the Board,” says Groves. When IR and the corporate secretary work closely together, she concludes, “it’s a really big opportunity for both.”